Recent teacher strikes in West Virginia, Kentucky, Oklahoma and anticipated strikes in Arizona have excited some in the labor movement who herald the strikes as a sign of a renewed era of union power.

More likely, the strikes are a concentrated attempt by government unions to pressure the U.S. Supreme Court to rule in their favor in Janus v. AFSCME Council 31.

The plaintiff in that case, Mark Janus, is an Illinois state employee who rightly contends that it is unconstitutional for the state to force him to financially support the highly political American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees as a condition of his employment. A decision in the case is expected in June, and most unions anticipate a loss.

One of the key union arguments in Janus is that the infringement of employees’ First Amendment rights that results from forcing them to pay a private, political, third-party entity against their will is justified by the “compelling interest” of state and local governments in preventing labor unrest.

David Frederick, the attorney for AFSCME Council 31, explained it this way in oral arguments before the Supreme Court:

[Agency] fees are the tradeoff. Union security is the tradeoff for no strikes. And so if you were to overrule Abood [and make union dues payment optional], you can raise an untold specter of labor unrest throughout the country.

However, as Janus’ attorney Bill Messenger pointed out in response, this argument,

…would make agency fees effectively a form of protection money, the idea that the government needs to force its employees to subsidize unions or otherwise the unions will disrupt the government, and I submit that’s not an interest that this Court can accept as a compelling one for infringing on individuals’ First Amendment rights.

Legal arguments aside, the fact is that strikes by public employees in right-to-work states where union membership and dues payment are voluntary are relatively rare.

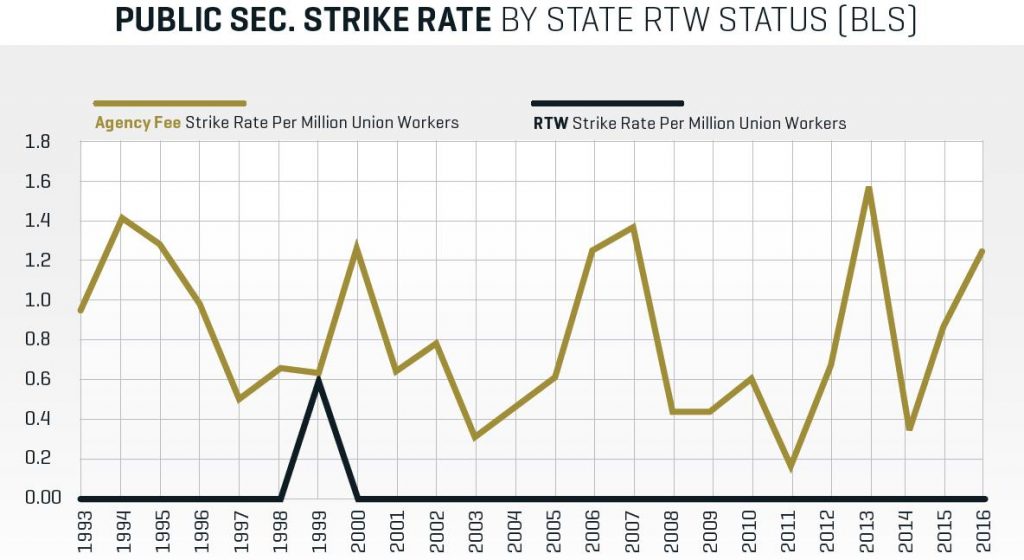

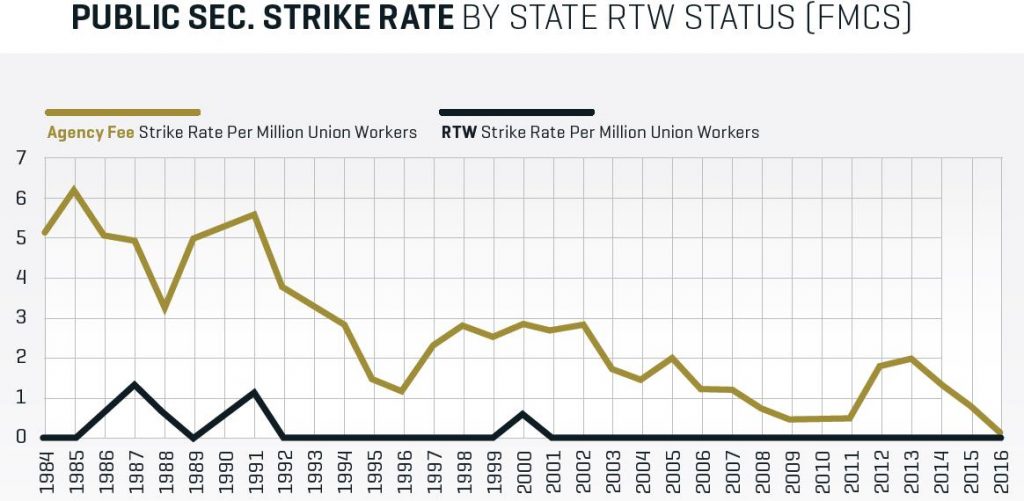

A recent Freedom Foundation study examined two federal databases of strikes and work stoppages going back to 1993 and 1984, respectively. The Freedom Foundation analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics data indicated that government employees in agency-fee states went on strike at 27 times the rate of public employees in right-to-work states.

Analysis of a similar database maintained by the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service indicated that public-sector workers in agency-fee states went on strike at a rate 17 times greater than that of their counterparts in right-to-work states.

By historical standards then, the recent spate of large-scale teacher strikes in West Virginia, Kentucky, Oklahoma and Arizona — all right-to-work states — is something of an anomaly.

While labor activists like to think of the strikes as a sign of a resurgent labor movement, a recent article by Jason Walta, senior counsel for the National Education Association, the largest teachers’ union in the country, strongly indicates otherwise.

Walta’s article for the liberal American Constitution Society admits that the recent strike activity has “few precedents in recent memory.”

Walta continues,

The scene playing out now should put the Supreme Court on notice as it considers a ruling in Janus v. AFSCME. It is no coincidence that West Virginia, Oklahoma, Kentucky, and Arizona are all so-called ‘right to work’ states with weak or no public-sector collective-bargaining laws.

No coincidence, indeed.

“It doesn’t have to be this way,” Walta warns, “But if the Court decides otherwise—and constitutionally enshrines a nationwide ‘right to work’ law throughout the public sector—educators, other public servants, and the communities they serve won’t be silenced. What’s happening in Oklahoma, West Virginia, Kentucky, and Arizona could be coming soon to a state capital near you.”

If that doesn’t sound like a threat, I don’t know what does (the Cambridge Dictionary defines “protection money” as, “money that criminals [unions] take from people [taxpayers] in exchange for agreeing not to hurt them or damage their property”).

While Walta’s article effectively gives the game away, it’s worth noting that, while teachers have various reasons for striking state to state — pay levels, pension benefits, class sizes, etc. — none of the protesting teachers in any of these states are publicly demanding the ability to force their colleagues to pay union dues. And teachers in right-to-work states with higher levels of teacher pay and education funding aren’t striking at all.

Lastly, while teachers can generally go on strike without fear of losing any pay, since the missed school days have to be made up at the end of the year, most other public employees working year-round jobs don’t have this luxury. Unsurprisingly, strikes by non-teacher public employees are exceedingly rare.

Thus, government unions are not only trying to justify violating public employees First Amendment rights by engaging in what amounts to a protection racket against taxpayers, they are also manipulating the legitimate workplace concerns of teachers in a handful of states to support union executives’ larger agenda and financial interests.

In short, government unions are behaving about as they always do.